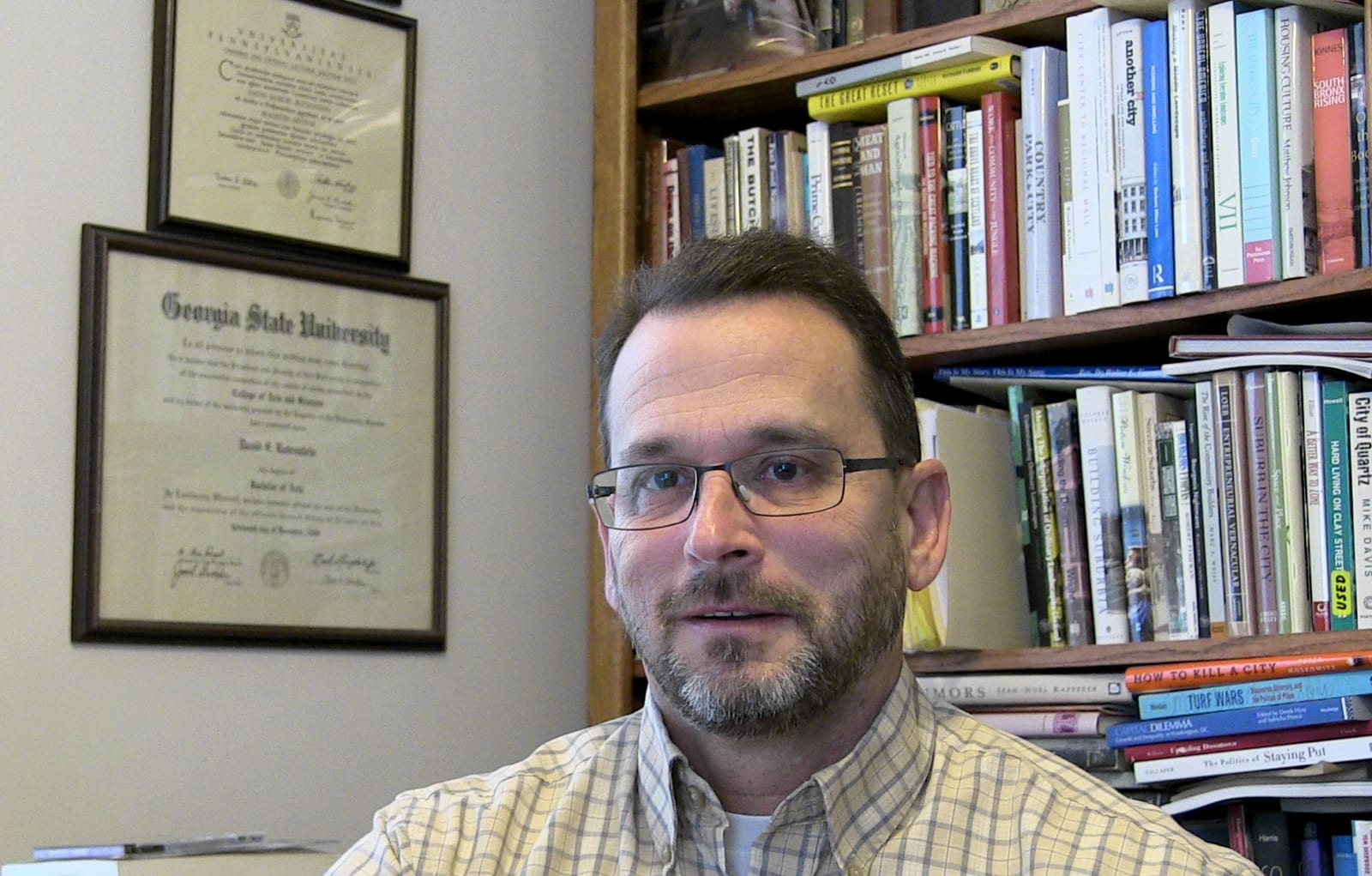

Editor’s note: The Tito Family homestead which still stands on Fifth Avenue in Uptown has been nominated for historic designation in the city of Pittsburgh. The author of this story, David Rotenstein, is also a consultant on the nomination.

The Tito Boys, as they were known in the Uptown and Soho neighborhoods, were among Pittsburgh’s best-known bootleggers. Joe, Tony, Ralph, Robert and Frank were born to Italian immigrants Raphael and Rosa Tito between 1890 and 1905. By the early 1920s, they had become involved in organized crime and were close with Gus Greenlee, one of Pittsburgh’s most notorious racketeers. They are fondly remembered as the entrepreneurs who invested in a flagging Latrobe brewery and for introducing Rolling Rock beer.

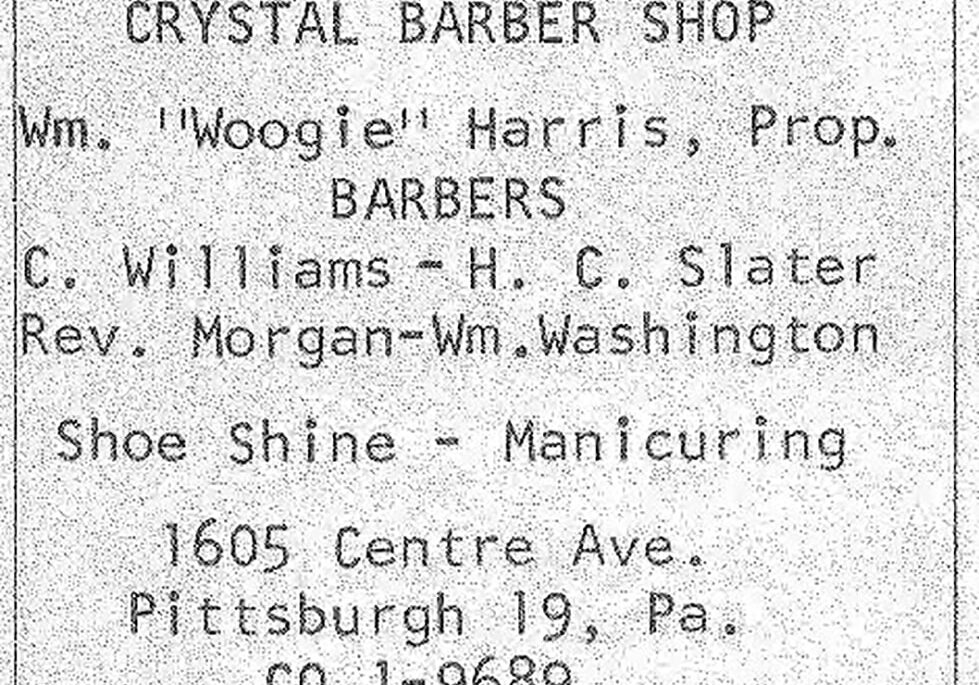

Learn more about Pittsburgh mob legends Gus Greenlee & Woogie Harris

Isaac Morshun was a Russian immigrant who moved to Pittsburgh before the prohibition. Morshun was also a well-known bootlegger.

After Joe and Robert died within months of each other in 1949, the small-time racketeer saw an opening to try to get some significant money from the family. This is the story about that shakedown.

The Tito Boys from Uptown to Latrobe Brewing

Raphael Tito arrived in Pittsburgh in 1888 and rented a home in Bloomfield. He worked lighting streetlamps, and, by 1894, had saved enough money to buy a home in the city’s Uptown neighborhood. Over the next three decades, Raphael bought additional properties for his growing family, creating a small colony for his clan along Allequippa and Gazzam streets.

Raphael and Rosa raised their eight children in the Gazzam Street home. When Prohibition began in 1920, the five Tito boys were in business together. After making money as hucksters selling vegetables and running a poolroom, they bought a small fleet of trucks and began calling their firm “Tito Brothers.” They claimed to be in the “hauling” business and their most profitable loads seemed to be liquor.

Joe, the oldest, became the ringleader. He was prosecuted in federal court multiple times in the 1920s. In this period, he became business partners and friends with bootlegger-turned-numbers baron Gus Greenlee. Stories have circulated in the Hill District since the 1930s that Greenlee taught Joe how to run a numbers racket.

“The Titos and Gus were just as tight as brother and sister,” Charles Greenlee, Gus Greenlee’s brother, told University of Pittsburgh historian Rob Ruck in 1980.

When Greenlee decided in 1931 to build a sports stadium for the Pittsburgh Crawfords, his Negro Leagues team, the Tito brothers were among his biggest investors. Joe Tito became an officer and major shareholder in the Bedford Land Company, the entity formed to build and operate the stadium. Joe’s younger brother, Ralph, who owned the Cabin Grill downtown, got a lucrative concessions contract for the new Greenlee Field. Greenlee Field is hailed as the first Black-built and owned professional sports stadium in the United States.

Latrobe Brewing Company: Money laundering, Rolling Rock beer and rackets

In 1932, the year Greenlee Field opened, the Titos bought the Pittsburgh Brewing Company’s Latrobe assets, which included the company that had been doing business as the Latrobe Brewing Company (during Prohibition, the Latrobe Beverage Company). It was conceived as a money-laundering operation that became more successful than any of the family could have imagined, says Rona Peckich, one of Joe Tito’s great-great-niece. Frank Tito managed the company’s first Pittsburgh beer distributorship located in a brick building behind Joe’s Fifth Avenue home. That’s where, in 1935, the family began selling its Rolling Rock beer.

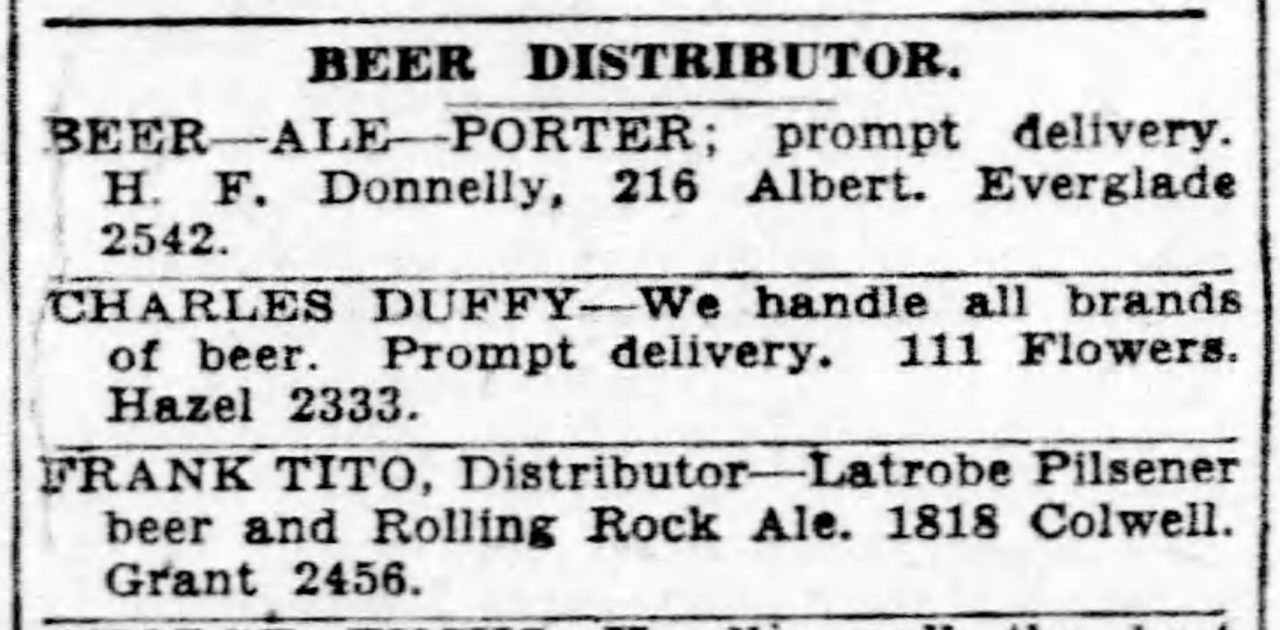

Most histories and the Rolling Rock beer website give 1939 as the date it was introduced, but Frank Tito was advertising it in Pittsburgh newspapers by early 1935.

Joe was Latrobe Brewing Company’s vice president and Robert was its secretary. Both had become very wealthy by the time they died in the spring of 1949, each leaving estates worth more than $100,000 (more than $1 million in 2021). They had shed their underworld origins and were among Pittsburgh’s most prominent residents when they died.

Isaac Morshun: A long list of bootlegging arrests

Isaac Morshun — Ike to his friends — was born in 1896 in Russia and emigrated to the United States in 1913. If Morshun’s 1932 petition for U.S. citizenship is to be believed (and there are lots of reasons it can’t be), he got to Pittsburgh in June of 1922. Six months later, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported that he had been arrested after being caught with “a large quantity of alleged contraband liquor and six stills.”

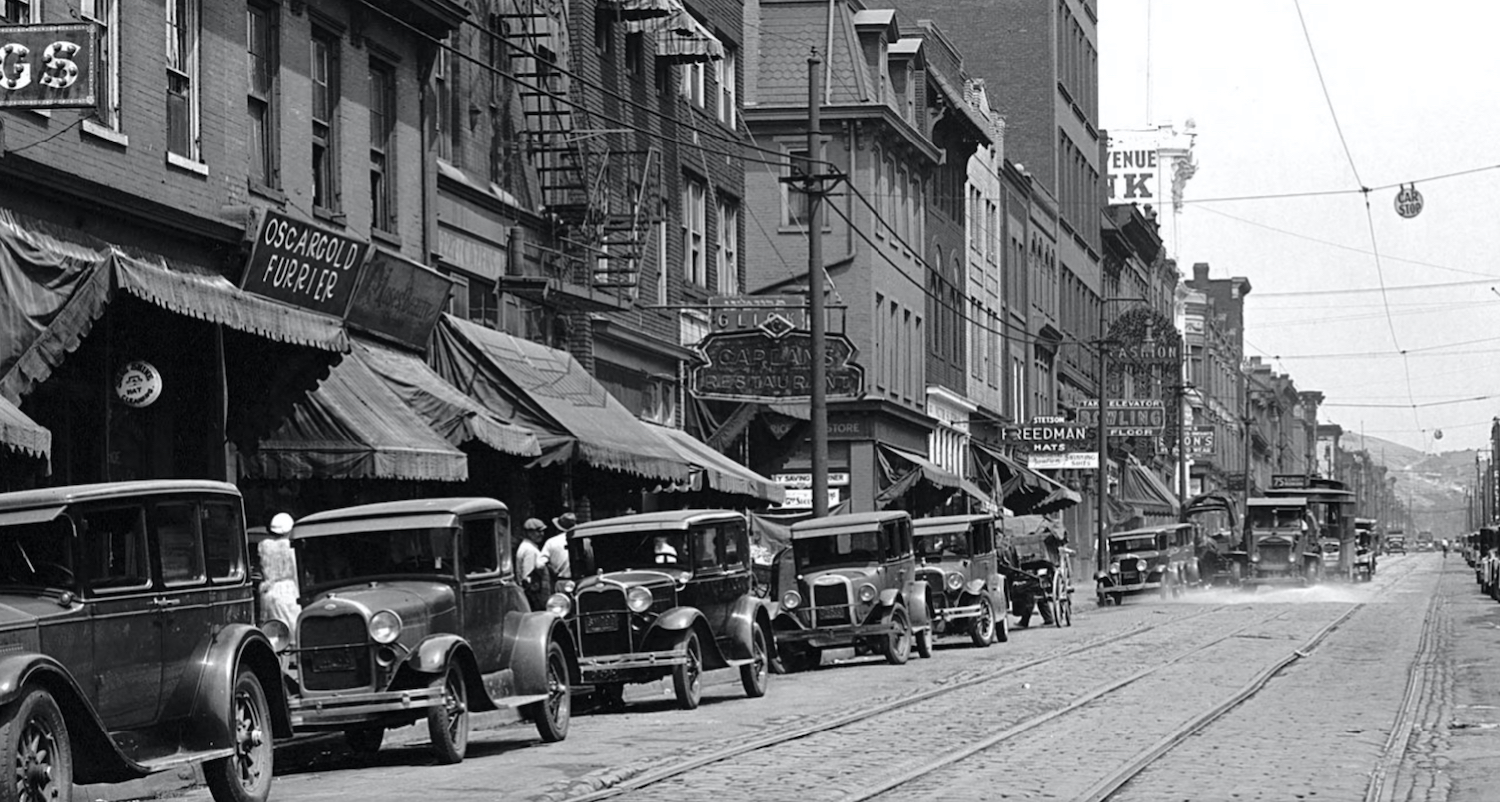

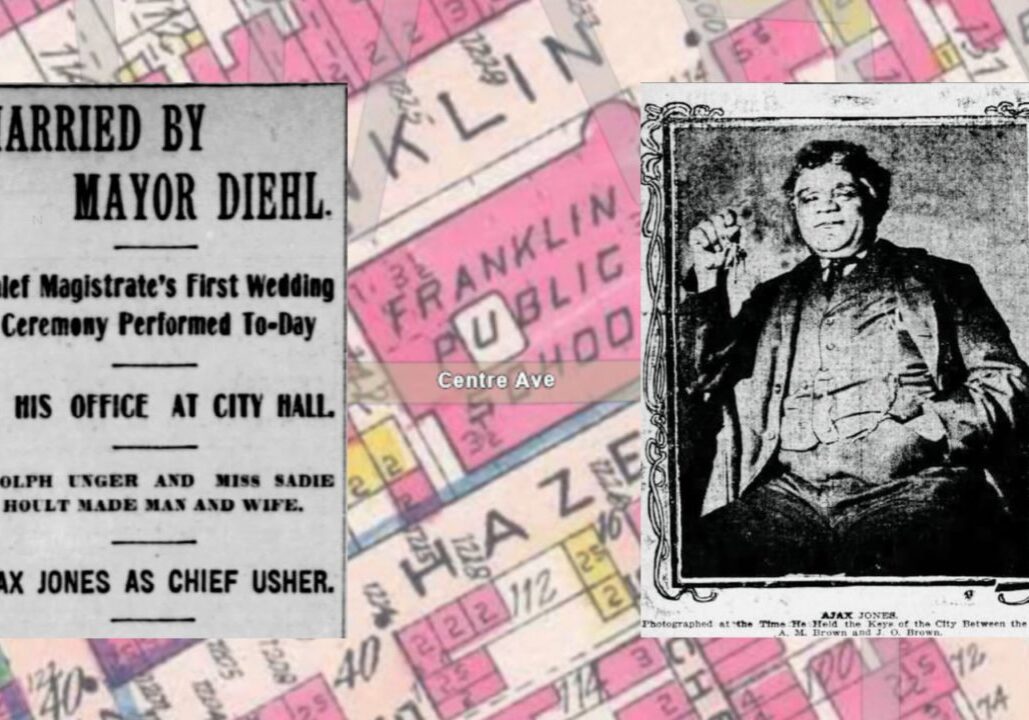

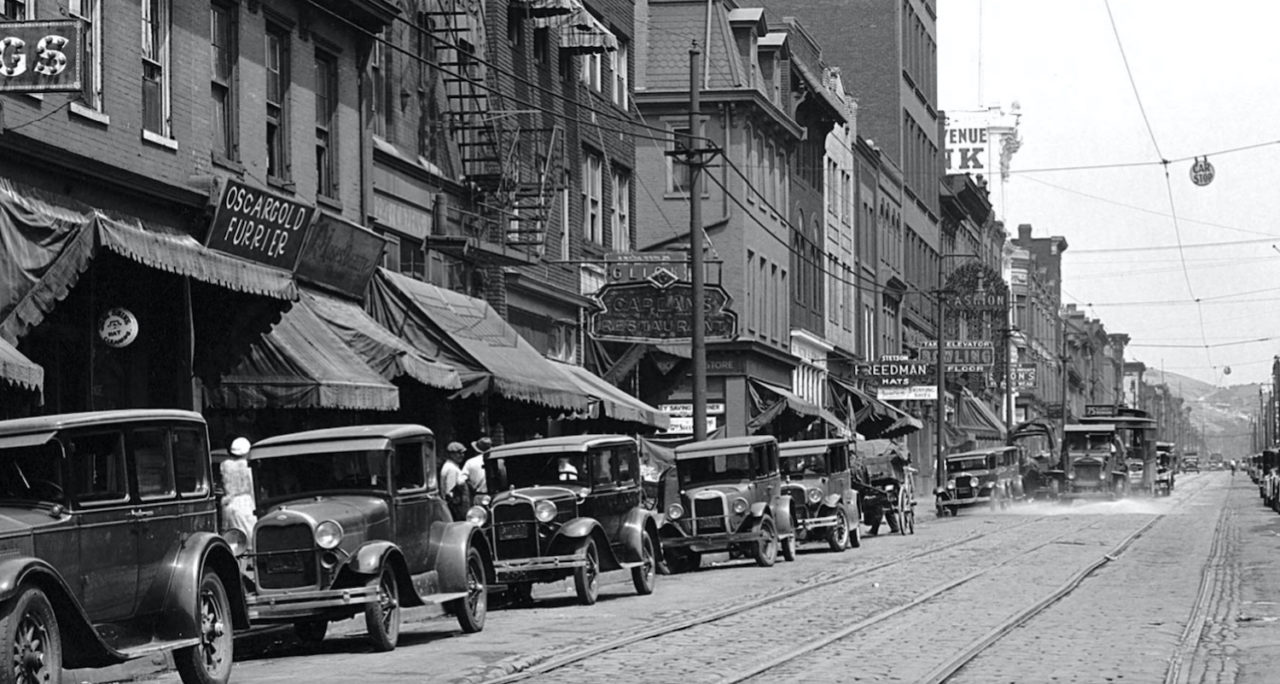

After moving to Pittsburgh, he spent much of his time living and working in the Fifth Avenue corridor, an area the city’s Italian and Black residents called “Jewtown” for its large number of Jewish-owned businesses. It was a heavily congested area where bootleggers and gamblers plied their trades in the pool rooms and restaurants packed in among clothing wholesalers and other merchants. If Wylie Avenue, with its Black-owned nightclubs and eateries backed by bootlegging and gambling money, was Pittsburgh’s glamorous stroll, then Fifth Avenue was Pittsburgh’s syndicated crime’s back office.

Morshun fit in well among the other entrepreneurs there profiting from vice, people like the Tito brothers. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Pittsburgh’s press reported on Morshun’s many bootlegging arrests. One time in 1933, Morshun was beaten and robbed of $1,400. The next year, federal agents arrested Morshun and his wife in a Shadyside apartment building where they seized 481 gallons of alcohol and 36 cases of whiskey — all of it stored in a basement locker.

By 1939, Morshun had racked up enough busts that the feds had had enough. A judge ordered that Morshun’s citizenship be revoked. Morshun had lied about not being arrested for bootlegging prior to applying for citizenship and officials added, “he had been arrested several times since for similar infractions.” The judge agreed and canceled Morshun’s citizenship, writing, “Isaac Morshun did not behave as a person of good moral character.”

Attempts to shakedown the Tito estate for $3000

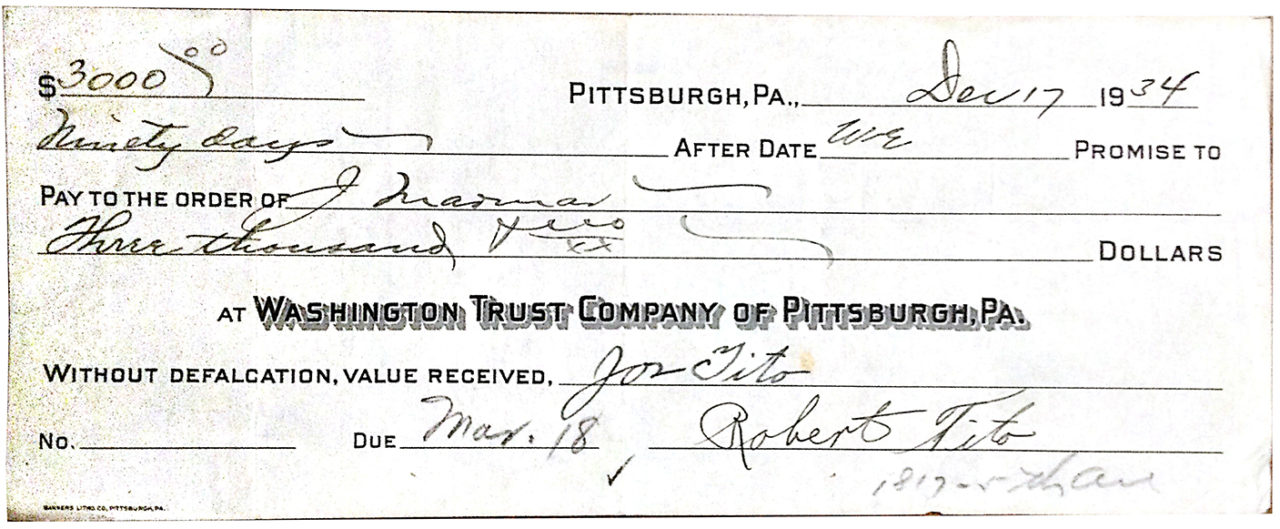

After Joe and Robert Tito died in 1949, Morshun’s attorney, Abraham Pervin, filed a claim declaring that the Titos owed him $3,000 — the amount remaining from the alleged original debt. Morshun asserted that the Titos had borrowed $15,000 from him in the late 1920s. He produced a banknote that the brothers allegedly signed in 1934.

At the time the note allegedly was signed, Morshun had been living in a rented apartment above Caplan’s Restaurant at 1229 Fifth Avenue — his abode for many years before and after the note’s date, according to newspaper articles reporting on his many arrests. Joe Tito was living in the family’s spacious Fifth Avenue brick Queen Anne and Robert Tito was living in a Soho house. Just one year earlier, the brothers had bought the Latrobe Brewing Company.

There was a hearing to adjudicate the validity of the $3,000 claim in December 1950. Morshun, through his attorneys and witnesses, said that he and the Titos had more than two-dozen meetings in Caplan’s Restaurant where money changed hands over lunch and friendly conversations. Morshun’s witnesses claimed to have seen the money and heard the conversations.

Pervin called five witnesses, including Morshun. Sol “Sollie” Rudkin and Joseph Engelsberg were Pervin’s two key witnesses. Rudkin was a bootlegger who had been arrested with Morshun. He was married to Josephine Caplan, daughter of Caplan’s Restaurant owner, Louis Caplan. Rudkin managed the restaurant for his in-laws. In 1936, Morshun and Rudkin were one of 15 suspected bootleggers snared in a federal investigation that involved wiretapping and a secret federal grand jury.

Attorneys Robert Jarvis and J.I. Simon represented the Titos in the hearing. Their defense and a blistering opinion by Judge P.J. Boyle shredded Morshun’s claim and the credibility of his witnesses as well as the $3,000 claim’s validity.

The numbers don’t add up

Joseph Engelsberg, who was close to Morshun, testified that he had known Joe Tito for about 35 years and Robert for about 25 years. According to the testimony, Engelsberg served as Morshun’s financial advisor. “He asked my advice about this Tito Loan,” Englesberg answered under cross-examination.

Englesberg said that he frequently met with the Titos on Morshun’s behalf — Joe and Bob, he called them — and Morshun at Caplan’s Restaurant. “Whenever there was any exchange of moneys between the Titos and Mr. Morshun, Isaac would manage for me to be around,” Englesberg testified. “We had lunch together.”

Under cross-examination, Tito attorney Robert Jarvis asked Englesberg if Morshun had money to lend in 1934. “As long as I know [sic.] Isaac he had a lot of money — then, before and after,” Engelsberg replied.

In reality, Morshun didn’t have money to lend and the Tito brothers were likely not looking for a loan. Jarvis, the attorney for the Tito estate, then produced records from a 1936 court proceeding. Morshun had been jailed for seven days for failing to pay a civil judgment against him. He filed a petition for release under Pennsylvania’s “Insolvency Act.” Morshun claimed that he was unable to pay the judgment because he was broke: “At the time of the arrest and for two years preceding the said arrest your petitioner has not been able to earn practically anything.”

Neither side in the hearing introduced Rudkin’s prior involvement with Morshun in bootlegging. The bootlegger turned restaurant manager testified that Morsun ate all of his meals in Caplan’s: “That’s right. That was his home.” Rudkin also told the court that he had frequently seen Morshun and Engelsberg meeting with the Tito brothers over lunches in the restaurant. “I joked with them many times, because I was very close with all of them,” Rudkin said.

The judge cut short Rudkin’s testimony after Morshun’s attorneys couldn’t prove that Rudkin had witnessed the Tito brothers signing the note in 1934.

Last up was Morshun himself. After being sworn in, the Titos’ attorney objected by asserting that Morshun was “incompetent to testify.” The judge agreed, saying, “The proof that has been offered in this claim is not of very high standard.”

Criminals’ Codes

In a scathing decision issued four months after the hearing, Judge Boyle noted that the note was made out to a fictitious name, “An alias of the claimant.” Morshun’s own words in the petition he filed to be released from jail in 1936 were damning. In the detailed accounting of his assets and liabilities to support the 1936 petition, Morshun didn’t include a substantial debt owed him by the Titos as an asset.

“To allow the claim on this note would be to endorse the fraud which the claimant committed on the Common Pleas Court when he procured his discharge in 1936,” Judge Boyle wrote. “The proof offered in support of the claim is legally insufficient. The claim will not be allowed.”

Morshun’s bid for the Tito money had failed. He didn’t appeal nor did he even request the return of the note allegedly signed by the Titos that had been entered into evidence.

The Titos were no longer allegedly settling their disputes with bombs, guns, and icepicks by the time Morshun tried to shake them down. They were wealthy men and they used lawyers to dispense with their problems. Their names are indelibly etched in Pittsburgh’s history.

His criminal career continued for another decade with additional bootlegging and numbers arrests. In 1958, Morshun was convicted of hijacking $20,000 worth of cigarettes. That case took an unusual twist when Morhsun was arrested after leaving court. He had made a false claim that had been approached by someone offering to “fix” his trial and he lied about telling two police officers about it — while also admitting that the extortion attempt took place as he was writing numbers outside of a “Fifth Avenue restaurant.”

According to Allegheny County criminal courts records, Morshun was paroled in 1962. Less than a year later, he was arrested and charged with bootlegging. He disappeared from the historical record after being found not guilty in 1964 and has been forgotten.

Additional Resources

- Robert Ruck. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh. Illini Books ed. Sport and Society. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993. [Amazon, Bookshop.org]

- Nick Trumpo. “The Latrobe Brewing Co.: Rolling Rock and More,” Pennsylvania Center for the Book.

- Rolling Rock beer website.