Photos by Michael DeMocker

The legacy of Darryl Reeves’ African ancestors is in plain sight, sealed into the wrought iron of the French Quarter. From St. Louis Cathedral to the Cabildo, the New Orleans native has dedicated his career to restoring the iron artistry of the past while forging a future for the historic trade.

Few still know the trade, Reeves says, counting himself among the small handful of Americans who work as professional blacksmiths.

But in a centuries-old city, it’s an art that’s still alive, keeps Reeves busy, and above all, he says, earns him respect — just like generations of Black New Orleanians who came before him.

“A trade like this, I do it for a living. I’m a professional, but this is not work to me,” Reeves said. “This is my playground. This is where I come to play.”

Reeves has spent the past 50 years as a restoration blacksmith, fixing some of the most iconic metal structures in the city. Most of those, he says, were made by west Africans and still bear the marks of their culture. And their resistance to oppression.

“Every nationality had their own way of doing something. I can tell you what nationality fabricated the piece by looking at it. That’s how long I’ve been around,” Reeves said.

HOW IT STARTED

The story of blacksmithing in New Orleans begins with the founding of the city over 300 years ago. French settlers made plans to turn the piece of land on the banks of the Mississippi River into a sprawling community, but they didn’t have the manpower or skills to do it themselves.

So they turned to African slaves.

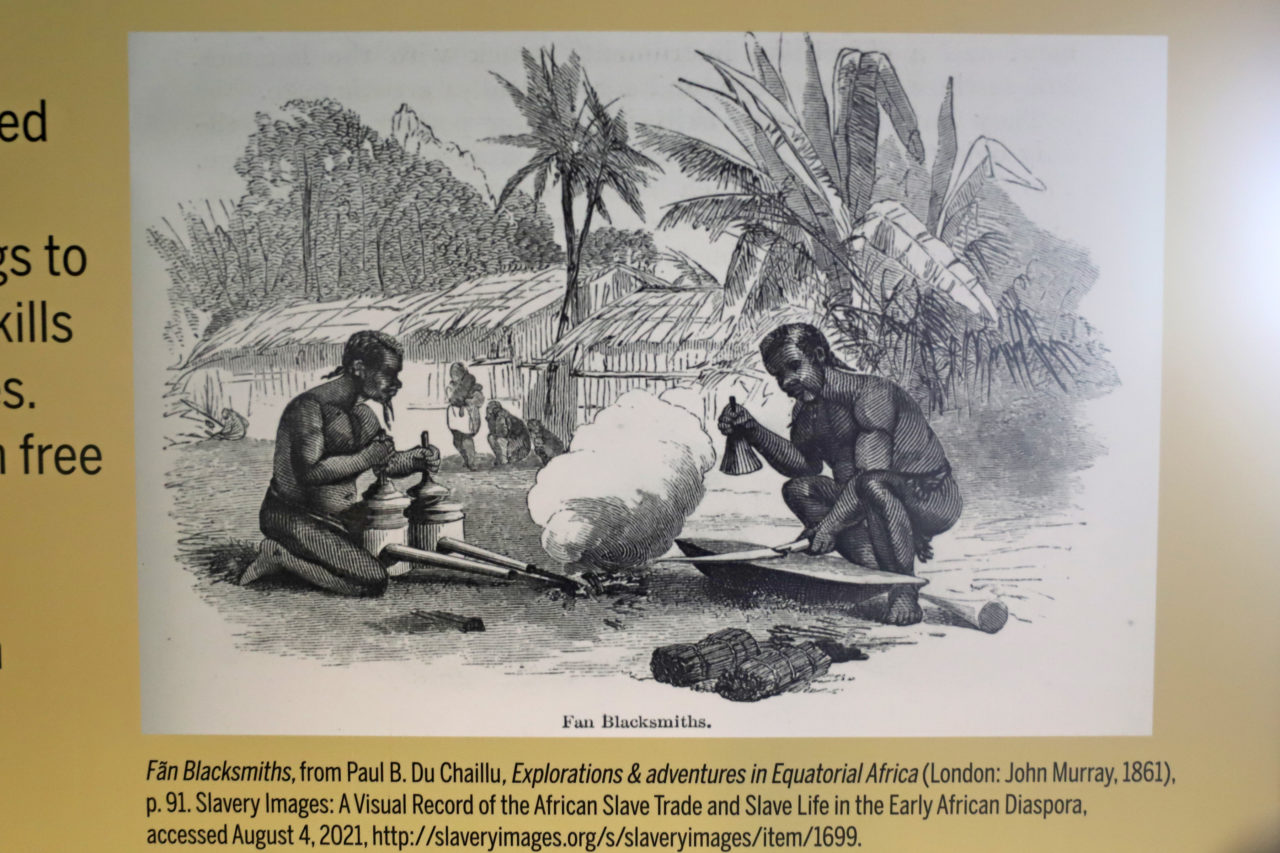

Europeans knew that Africans had a history with ironworking and a deep understanding of the skills. Dating back to the early fifteenth century, Portuguese explorers saw blacksmiths’ art at the mouth of the Congo River.

Because of their established knowledge of metal work, the French brought over slaves from west Africa and west-central Africa to support a rapidly growing need for metal work in their American colonies in the early 18th century.

The number of skilled craftspeople continued to grow in the latter half of the century when tens of thousands of free people of color found refuge in New Orleans and cities on the East Coast of the United States following revolutions in Haiti and Cuba. This surge of craftspeople in New Orleans helped to restore the architecture after two fires nearly destroyed the city in 1788 and 1794.

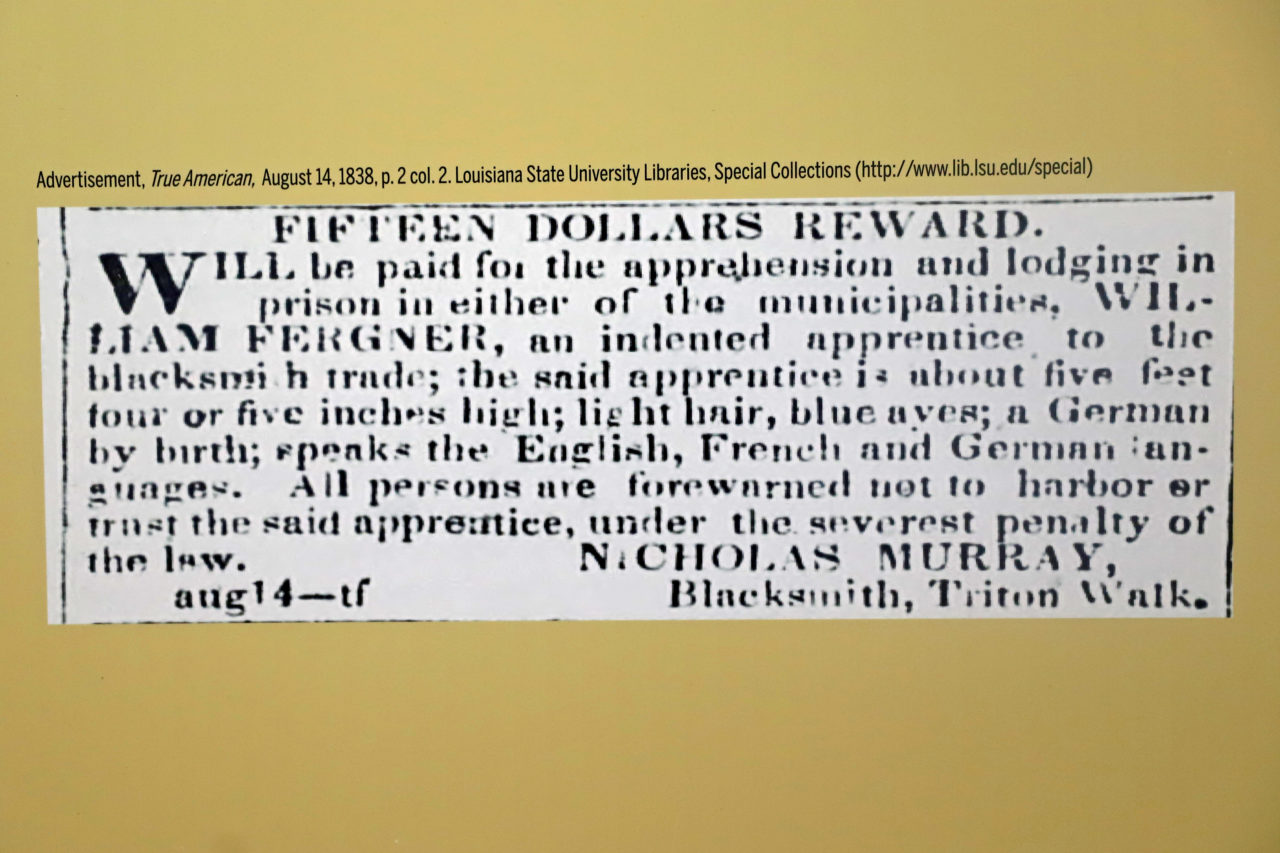

The work of blacksmiths in New Orleans was an integral part of daily life, like in other emerging American cities. Their services included everything from making doors and locks to forging tools to shoeing horses. Because of this, blacksmith shops were spread out every few blocks in the city.

“You couldn’t have a town without a blacksmith. You couldn’t have a town without a doctor, and a lot of times the doctor and the blacksmith were the same person,” Reeves joked.

Black communities in New Orleans heralded blacksmiths as leaders, both because of their physical strength and cultural capital. These blacksmiths were often at the forefront of rebellions in the 18th and 19th centuries.

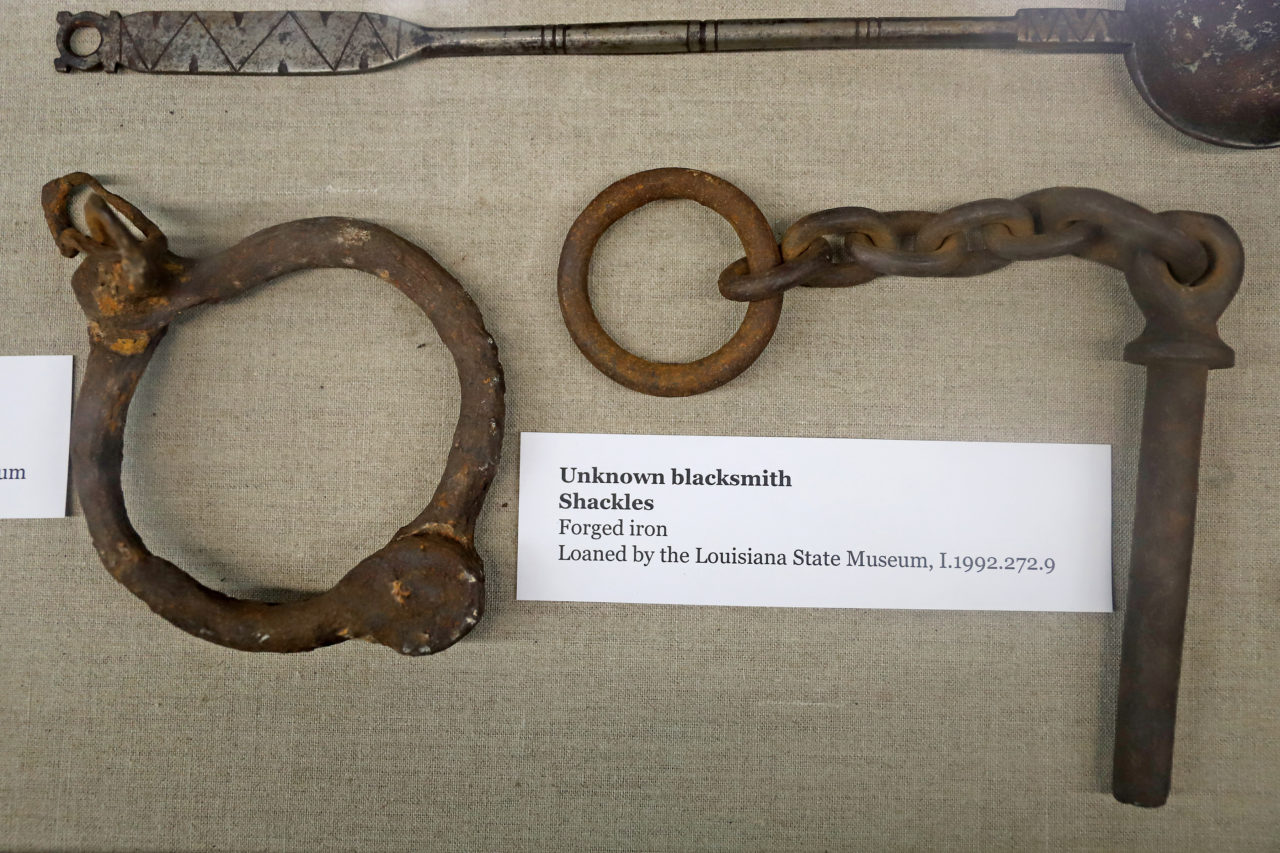

Despite their perceived value, blacksmiths of color were forced to participate in the suppression of their own people by having to make handcuffs, shackles and jail bars for prisoners and the enslaved.

THE SPIRIT OF AFRICA

In the new world, Black blacksmiths in New Orleans found a way to secretly resist their oppressors by honoring their own histories and spiritual practices through their craft.

Iron pieces created by blacksmiths of color in the 18th and 19th centuries are covered with symbols from their home countries. Circular patterns that signify the regeneration of life, Ghanian adinkra symbols and Haitian vévés were forged into the craftsmen’s work as a way of covertly speaking to their people.

“People look at [wrought iron], and they see nice designs, but a lot of those designs mean something, and it’s a language that they brought from West Africa,” Reeves says.

To see it, look no farther than St. Louis Cathedral. Two of the three spires atop the church feature sankofa symbols from Ghana. The heart-shaped motif means “return and get it,” which encourages people to learn from the past.

Symbols like the sankofa are so prominent in New Orleans architecture because free and enslaved people of color rebuilt most of the city after the great fires of 1788 and 1794. More than 70% of the single-story cottages that lined the streets were replaced by two-story townhouses.

The new style of buildings introduced the use of the wrought iron balconies and railings still visible across the city today. Blacksmiths blended African, French and Spanish elements to create the designs.

“I look at the symbolism in ironwork much as culinary historians look at the ingredients in gumbo,” Jonn Hankins, founder of the New Orleans Master Crafts Guild, said. “The okra that is in gumbo doesn’t just appear accidentally. That’s what I’d like to bring to a wider recognition of the role that people of color have played in what we find so unique and pleasing about the built environment of New Orleans.”

By 1825, the distinguished culturally inspired iron designs started to decline because of the growing use of cast iron. Small blacksmith shops were replaced by large industrial foundries. These foundries quickly produced cast iron with patterns from catalogs, which made unique iron designs harder to find.

ARTISTRY IN IRON

After the 1800s, blacksmithing became somewhat of a lost art. The number of craftsman who could create the historical iron designs dwindled, and the oral histories of blacksmiths of color were lost in time. But now, there is a revived effort to tell the stories of the people who built New Orleans.

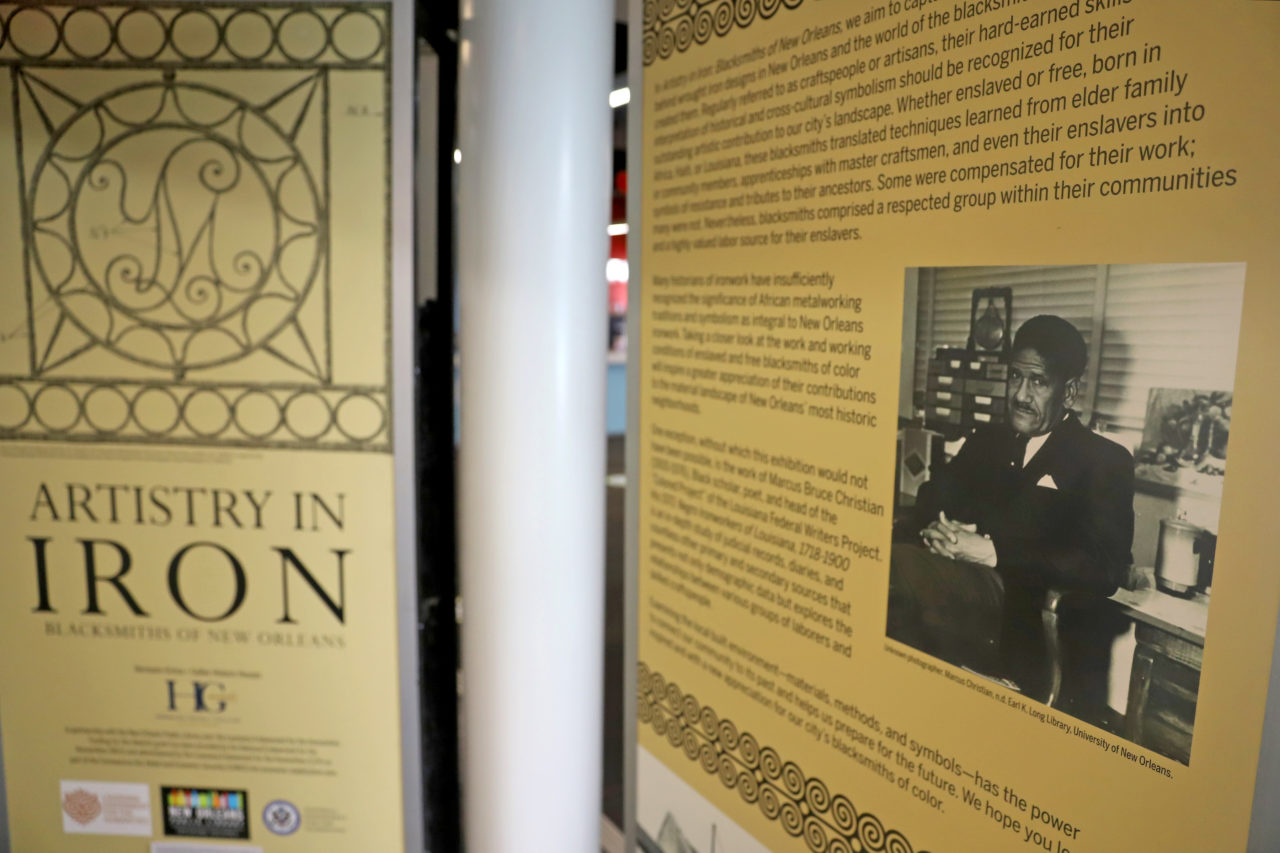

Artistry in Iron: Blacksmiths of New Orleans is an exhibition that explores the origins of wrought iron designs in New Orleans and uncovers the identities of the craftsmen who created them.

The exhibit, which was curated by Katie Burlison of the Hermann-Grima + Gallier Historic Houses, has been on display for the past few months in New Orleans public libraries. Burlison says Hermann-Grima + Gallier Historic Houses wanted to put the exhibition in local libraries to make it more accessible and get its message out to a large swath of people.

“It being at the library is because we’re the information place. We’re the place you go for information, whether it’s educating yourself or getting to see something that’s already there like an exhibit, and I think that being able to get this out in the community is better for getting this information in front of people,” said Amanda Fallis, archivist for the New Orleans Public Library.

Hermann-Grima + Gallier Historic Houses specifically selected the Nora Navra Library in the 7th Ward and the East New Orleans Regional Library as temporary homes for Artistry in Iron: Blacksmiths of New Orleans to get the exhibition in front of Black communities that likely had connections to its subjects.

Tools and designs on display at the “Artistry in Iron” exhibit, a celebration of New Orleans’ Black Ironworkers at the East New Orleans Regional Library. (Photo by Michael DeMocker) A display at the “Artistry in Iron” exhibit, a celebration of New Orleans’ Black Ironworkers at the East New Orleans Regional Library. (Photo by Michael DeMocker) Shackles on display at the “Artistry in Iron” exhibit, a celebration of New Orleans’ Black Ironworkers at the East New Orleans Regional Library. (Photo by Michael DeMocker) A display at the “Artistry in Iron” exhibit, a celebration of New Orleans’ Black Ironworkers at the East New Orleans Regional Library. (Photo by Michael DeMocker)

“There’s an expression in New Orleans that if you want a good plasterer or a good carpenter, you need to get a 7th Ward craftsman, and that’s where they are,” Hankins said. “It was just so important to put it there because the people who could benefit from this a lot and see the work of their own relatives are right there in that community.”

The exhibit takes observers on a journey from Africa to Louisiana, explaining how the iron motifs molded over time, and displays iron artifacts dating back to the 18th century. There is also an online component comparing forging techniques of the past to the work that’s still done today.

“The goal was not necessarily to finish this story. It was really to reignite the conversation at a time where we really need to be having conversations about all of the important contributions of the Black community and people of African descent to New Orleans and the whole world,” Burlison says.

FORGING THE FUTURE

Hankins says exhibitions like Artistry in Iron: Blacksmiths of New Orleans demonstrate how blacksmithing is still a viable skill today.

“Now we see that, especially if you live in a historic city like New Orleans, there’s going to always be a need for top-skilled craftsmen and our people have family histories of excellence in those trades,” Hankins said.

The number of blacksmiths in the U.S. is estimated to have dwindled to between 5,000-10,000, with only 10% doing the work professionally, according to NPR.

As founder and director of the New Orleans Master Crafts Guild, Hankins works with blacksmiths like Reeves to ensure the upkeep of old iron structures and to pass down the skill to new generations of craftsmen.

“What made it so direly important was so many of the older craftsmen. We skipped a couple of generations, so people that have all that knowledge are like in their 70s or older, and so we have to pass this along to people in our community so we can continue,” Hankins said.

Reeves is trying his best to keep the trade alive. It’s simple enough, he says, if you’re just willing to learn.

“I’ve been training apprentices my whole career,” he said. “The ones that want to learn, I train.”